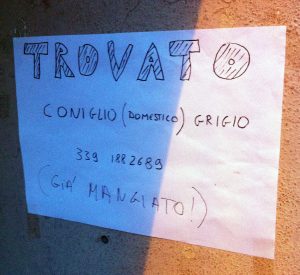

There’s a sign tacked on the wall outside our local pizzeria.

“Found. Gray (domestic) rabbit. Call this number”

And added underneath by someone: Already eaten!

And added underneath by someone: Already eaten!

Here in Tuscany rabbits are indeed a regular, and tasty, part of the menu. But the writer of this notice knows that a pet is a pet – hence the care given to mention that the bunny hopping around his house is “domestic”.

In Italian the word for “pet” is “un animale domestico” (a domestic animal) or “un animale di compagnia” (companion animal), this latter sounding only slightly less technical, giving some indication of the emotional value and importance of this human-animal bond.

Italy is a very public society and as no pet is a better companion than a dog, you see dogs everywhere here. They accompany their owners into shops, cafes, church services, on the bus and in the laps of car drivers.

These dogs were left to wait outside the famous butcher’s Falorni in Greve in Chianti – maybe their cones were a foil against the amazing smells during the 15 minutes their (German) owners were inside.

Eating out for lunch or dinner there’s often a dog – of any size – under a table or yapping close by.

And one local gelateria even offers ice cream for dogs.

I was at a children’s sports competition recently and along with half the parents of Florence I was crammed into the stands, indeed sitting on the concrete steps of what was probably the emergency exit. One woman left just after her daughter’s performance – she inched along the row, mobile in one manicured hand, the other holding the leash of her dog, the little yapper left to navigate his own way through the pedicured feet around him.

I can’t say much about the place of cats (or rabbits) in the family home, having come across few. A notable exception was seeing one in the supermarket once, a big furry gray thing ensconsed in the arms of its owner as he moved along the aisles.

Dogs are treated much the way children are – you don’t see them cuddled and spoiled all the time, they’re just along for the ride, even if that includes having their photo taken against the Ponte Vecchio. I haven’t done a spot check of how many Italian dogs have social media accounts (see #puppiesofinstagram) but I suspect overall it would be odder here than in other countries – many of these animals are still more for domestic purpose than simply objects of affection.

There are lots of ideas out there about how different languages interpret the bark of a dog. Scientists believe dogs can understand each other but people have different ways of hearing their bark: but what they seem to have in common is that they speak twice – such as “hav-hav” (Hebrew) or “wan-wan” (Japanese).

My husband and I have been living too peripatetic a life over the last 20 years to justify having a pet of any kind (apparently), but my 10-year-old and I are shameless dog people and share the habit of commenting on every dog we see on the street (or restaurant), especially older dogs who we’d love to adopt. At a recent lunch with friends in the country, my ears perked up when their neighbour mentioned her dog had just had 15 pups. Marking my interest she tried to convince me it would be a good idea to take one home – “well yes”, I told her, “I do have the time to walk it every day, yes we have a garden, yes half the family would love one, but it’s a really nice rented apartment… we couldn’t possibly”. “Oh! but it’s a dog”, she cried. “This is Italy, dogs stay outside!”

And indeed they usually do, at least in the countryside. Over the last couple of decades dogs have started to live more indoors, especially as city apartment-dwellers increasingly like to keep lap dogs like pugs and poodles. But many dogs around our small Tuscan town, are clearly less considered as pets than for traditional jobs like guarding, or weekend-hunting. And they stay outdoors – making sure they let us know they’re there, with a good old barking fit at 4am or 4pm. The ever spot-on Italy observer Tim Parks thinks this Italian need to keep the dog outside might be a hangover from people’s lingering collective memories of living under the same roof as cows and chickens.

The word “domestic” comes from the Latin word “domus” which means house, specifically the house of an upper-class Roman. It entered English as “dome”, or stately building. To me it feels like a formal word, indeed often with negative connotations. It can be associated with the mundane (domestic affairs), with servitude (domestics) and even with aggression and violence (domestic violence or abuse). This last is in fact an ongoing issue in Italy where societal norms deal badly with issues of partner violence, underreporting of abuse is low, and after some horrific high profile murders the media is currently talking of a nationwide emergency of “femicide”.

Un animale domestico – that’s how you say it in many languages. In English the term domestic animal is seen as a more technical term, referring to an animal that is not wild, but serves people and is dependant upon them. It’s even a legal term, have a look at this legal case I found about whether a camel should be considered wild or domestic.

But domestic animal just doesn’t sound as cosy as what we say in English – pet. What a lovely word that is! Just saying it makes you think of an animal that is not only domesticated but truly an emotional companion, for walks in the rain, sitting in the windowsill (tugging at the lace curtain), or just for being there to stroke/pet while you sit together (and watch the cricket on the telly).

The word pet actually came from the Scots Gaelic peata, tame animal, and its softness lends it associations of affection and caring. In Ireland, where it also came straight from the Gaelic, it’s used everyday as a charming appellation for children and friends (“ah sure listen pet, she was just chancing her arm”).

Down the road from our house is a farmhouse down off the road. We can look down over the high garden wall and say an encouraging hello to the unfortunate mutt that lives there. He’s left to himself all day long with a small scrap of garden between the wall and his owner’s house, his dirty mess left all over the ground and with little company. He can’t stop his tail from wagging sadly even as he keeps up the pretence of barking ferociously at you. A weary, empty bark.

In December we visited the cathedral of Lucca and I was taken by how many people were drawn to, (and drawing), this sculpture – the very beautiful funerary monument to the young Ilaria Caretto, carved by Jacopo della Quercia in the stunningly early date of 1406. At her feet sits a dog, not unlike a pug you’d find today in a flat in Kensington or Madrid. It may or may not be her dog, but it’s certainly intended by the artist to represent fidelity and undying love.

What more could you ask for in a pet?