“Brexit” is now a universally-known word and it is used as is, with no local translation. Brexit is Brexit in every language. Every language, but one – Irish.

The word Brexit was first coined in 2012, eight months before David Cameron announced he would be holding a referendum on the UK’s exit from the EU. The word was a natural successor to the word “Grexit” – the suitably-classical sounding name used to describe one solution to Greece’s massive debt issues. It’s not a technical term: but it’s a nickname – or actually a portmanteau – that has stuck, referring to the whole process of the UK leaving the EU.

“Brexit” won out over some weaker, and unpronounceable, alternatives, like “Ukexit” and the biscuity-flavoured “Brixit”. It was added to the OED in 2016 by which stage offshoot words were appearing: brexiteer, to brexit as well as Bregret, Bremain and remoaners. A child in Germany was even christened with it, according to the Express anyway.

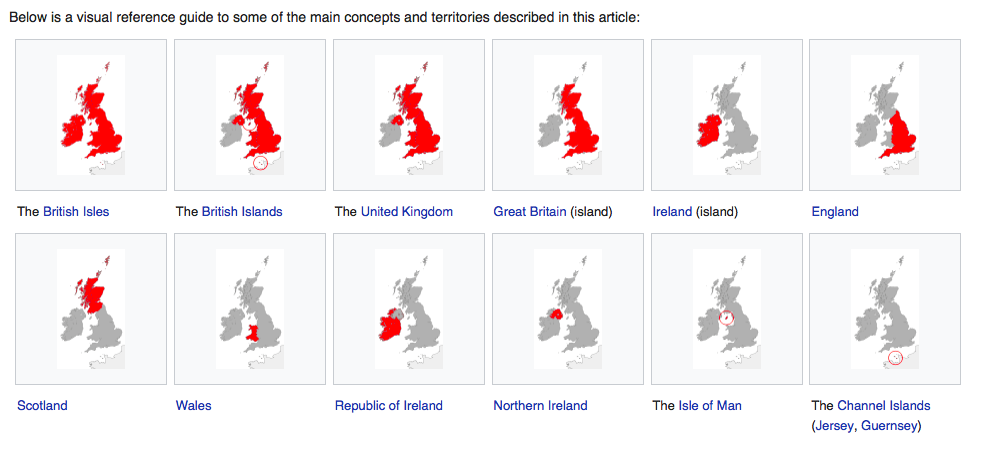

Take note that the term Brexit is not fully accurate – it is not just Britain that plans to leave, but the entire UK (which consists of Great Britain and Northern Ireland), though some of those individual elements voted to stay. I won’t get into the politics here. Really I won’t.

Names for possible EU-exits by other countries have thrown out some fun word-play. Here are some of my favourites:

- Nullgaria

- Fraurevoir

- Full (for Hungary)

- Quitaly

- Luxgettouttahere

- Forsakia

- Byerland (for Ireland)

So why haven’t other languages decided to adapt a local version of Brexit? Why didn’t, say, the French come up with their own word , as they usually do? What about languages that don’t typically use an X or where “exit” doesn’t work?

Could it be because Brexit was not meant to be a long-term thing? That it would be done and dusted quickly and easily? Or because only one country is likely to want to really pull out of the EU (even if they are still figuring out how, when, and even why)?

So how about the Irish – why did we bother to translate Brexit? First, some background:

The Irish language is spoken across the island of Ireland, north and south, and the Republic of Ireland is officially a bilingual country. I am far from being a fluent speaker, but I paid my dues and did the 14-odd years of it at school, (and yes I did do honours for the Leaving, to my credit).

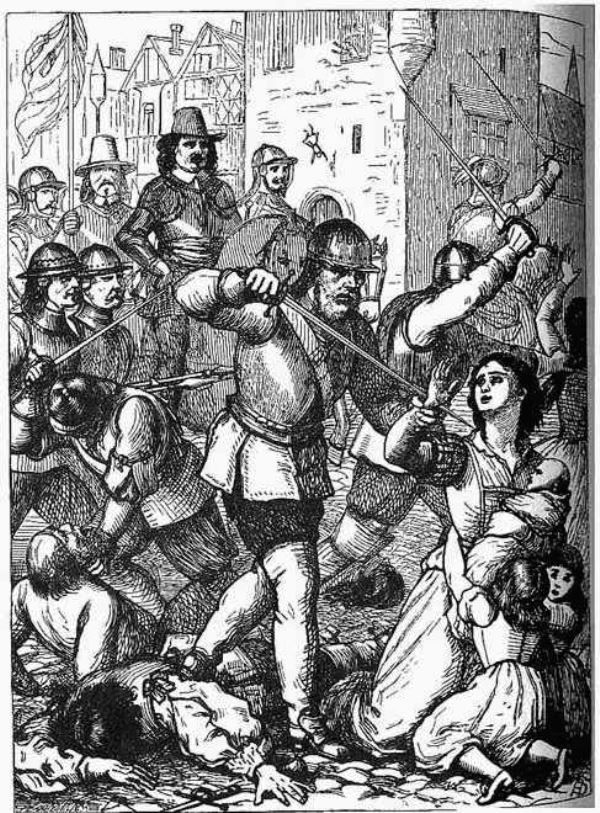

As a race, we’re known to be contrary – and as our own language was suppressed for several centuries by the English invader it’s no surprise that we like to adapt concepts to our own linguistic viewpoint. (You could say it’s making a statement, but who would actually notice, except us?)

So in the Irish language, there are in fact two words in use for Brexit.

The main media outlets in Ireland (which are English-speaking) of course use Brexit – and you should be aware that it’s probably more in the news in this country than even Britain, and more Irish people know what’s going on with the latest negotiations (or lack of) than many people in Britain. Why? Because no other country, even the UK itself, will be as directly affected by the exit when/if it happens. (A quick recap: trade, citizens’ rights, education, banking services, and the small matter of the Northern Irish border.)

As a bilingual country, Ireland has a thriving Irish-language media: one dedicated TV station, several radio stations, plenty of print and online publications.

And the Irish-language media chose not to use Brexit but came up with their own word: Breatimeacht.

“Breatimeacht” is the official Irish word used on the Nuacht (News). It’s a clever portmanteau that works well:

“na Breataine” = Britain

“imeacht” = leaving.

Irish-language guru Darach Ó Séaghdha, author of Motherfocloir and founder of the podcast, has written:

“some critics have pointed out that translation offers the opportunity for correction – it’s the UK that’s leaving, not the geographical entity of Britain. This has led to Sasamach being more popular in some quarters (Sasana, England, amach, out).”

This secondary word – Sasamach – is now being used (first coined by @tuigim) and I think it’s quite brilliant. Sasana (which stems from the word Saxon) refers to England, not Britain.

If you’re getting confused at this stage about UK/England/Britain/British Isles, here’s a handy quick guide:

The Irish word for an English person is “sasanach” and it’s a word that has appeared in many songs and poems over hundreds of years, often referring to how said Englishmen should best be booted out of Ireland.

Songs that evoke this kind of carry-on:

So – Sasamach is now doing the rounds to mean Brexit, as “amach” means out, so roughly speaking it’s a more forceful “Brits out”.

(Now, technically speaking “amach” means the process of moving out. Once you’re outside the word is “amuigh”. Maybe the word will need to change, in English too, but at this rate there’s no sign that they ever will be fully out.)

Language problems have started to plague other elements of Brexit in the last couple of weeks: the White Paper published in July was translated by the Foreign Office into 23 languages (including Irish) and the quality of translations was widely criticised, causing more British bemoaning about their level of language learning.

And for the Irish? Does our deliberate transliteration of Brexit mean we want it to happen, or not? Or are we just continuing our centuries-old habit of pushing around the confines of language?