There’s nothing like having a friend visiting to get you out and see new things in your own (current) city. And Dublin’s newest historic site – 14 Henrietta Street – which opened just last September, seemed like the perfect choice. It’s contained in just one building, you can see it only by a one-hour guided tour (booking recommended), and it’s in a part of the city I should know better. My father’s uncle, John Prunty, had a shop at 27 Dominick Street – but I’ll be telling his story another time.

This is Dublin’s first museum about its historic slums, which were only finally cleared in the 1970s. The word tenement – used in other cities like Glasgow and New York – refers to an older building split up into smaller flats, with a single entrance. But as these usually sprung up during the 19th century to accommodate the newly-industrial world’s growing city populations, tenements become shorthand for poor slums.

What the Dublin museum has achieved so well is a sense of the social history of Dublin through a sparse and innovative re-creation of this particular house’s history. It was built in 1720 as one of many grand city homes for a single wealthy family (plus servants) and 200 years later, its five floors were housing around 100 people.

The beautiful red and blue (reflected in the museum’s logo), are actually the standard colours used to paint the interiors of the tenement buildings. Reckitt’s blue and Raddle red, they were called, and no doubt associated with poverty.

The restoration work is superb: you can tell that was the case as soon as you walk in the entrance hall, a space which was completely restructured, and had a new staircase inserted. Have a look at the video below.

As the focus is on social history, it centres on the people who spent most of their time in the house – women and children. And that’s not something you see in a museum every day. As we hear about the first occupants – Lord Viscount and Lady Molesworth – we get a sense of their privilege. But also a reminder of class-blind cruelty as we learn of a later fire in their London home where she, by then a widow, lost several children in a house fire.

The gorgeous beech bed made specially for this house has been turned into a screen upon which is projected a specially-written poem, about mothers and babies, by poet Paula Meehan who was born in the Gardiner Street tenements. We are guided deliberately only through certain rooms, encouraged to take our time and sit on benches while we listen to stories – invited to imagine how things were, feeling life brought back into the different ages of the house.

Moving forward in the tour, and in time, we see how the grand rooms were sectioned off during the mid 1800s into one-room dwellings to be rented out to families of 7, 8, 11 people. None are left intact but we see traces of them, lines in the floor remind us of just how small the rooms were.

In the hallway we’re made to think of the smells and noises, the couples and strangers loitering in the darkness of a building whose front door was never locked, on a street, in one block, that housed thousands.

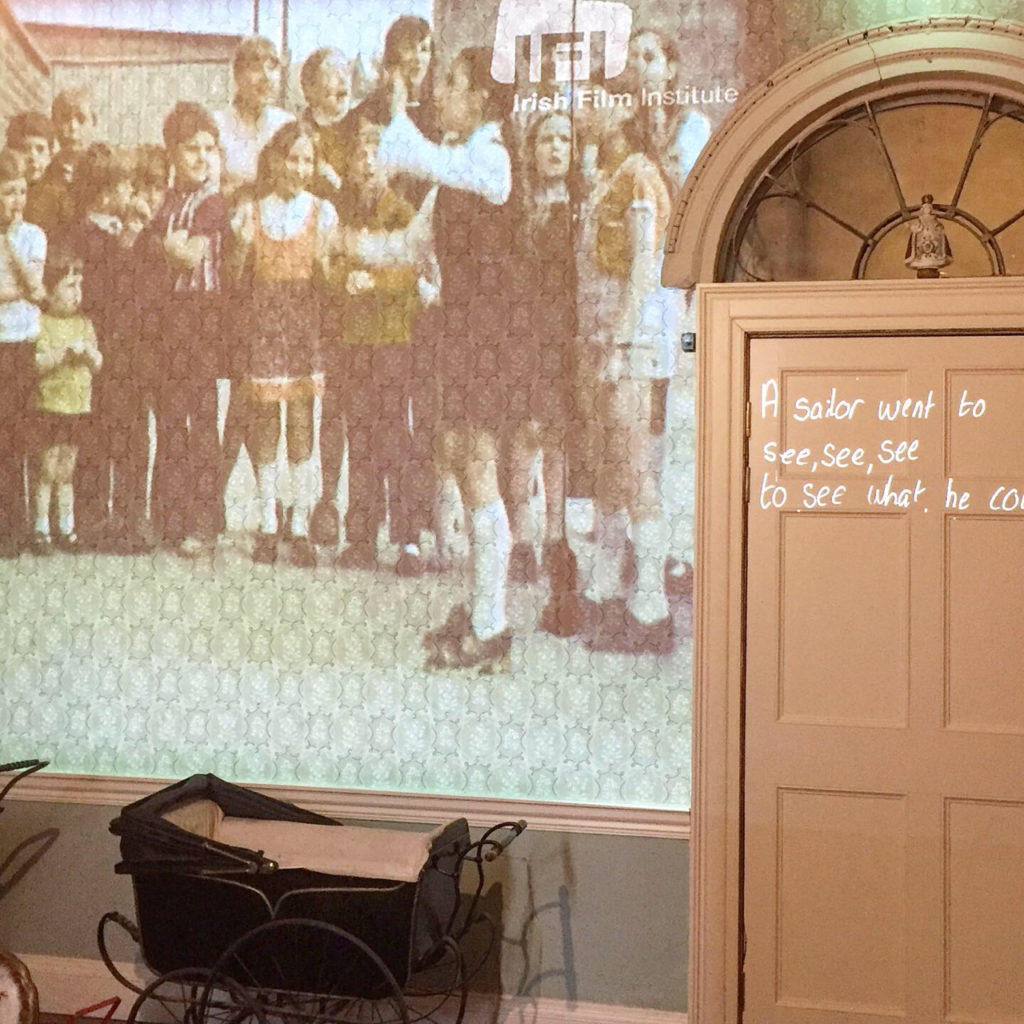

A nursery room starts to echo with street songs that most visiting school children are unlikely to have heard before.

Much of the interior is left feeling unfinished. Each inch of wall was carefully examined by the restorers but patches of peeling plasterwork and wallpaper are there as evidence of the house’s deep history.

The final room is a full replica of one of the final flats that remained before the house was shut down in the 70s. Inhabited by one person, it feels almost comfortable and it’s hard to imagine 10 people living in the same space. The family of this woman gave many mementoes to the museum, and they are of course continually collecting oral histories from everyone connected with the Dublin tenements.

Five floors of stories and memories and imagination, with immense care taken to preserve and interpret it, from grand drawing rooms to desperate poverty in the basement, this is one absolute gem you shouldn’t miss in Dublin.

The house has a great website and Facebook page with snippets of history. And they are of course on Instagram.

The architects’ site, Shaffrey, has more lovely photos.