It’s the end of an era. The tooth fairy is no more. The family myth was foiled yesterday morning by the youngest in the family. An upper tooth had fallen out at school and even though it was lost on the way home, she went ahead and left a book under her pillow (a habit our kids have/had was to leave the tooth inside a book). The only problem was, she didn’t tell us she did it because she wanted to send a signal directly to the tooth fairy. When that magical creature did not show up next morning, the game was up.

My daughter’s distress as the myth crumbled during my pre-breakfast dismal admission of subterfuge caught me by surprise – “so that tooth that fell down the armchair… you really did find it 4 years later didn’t you?”. And her distress made me remember just how young she is. When you’re only nine, why wouldn’t you want to hang on to that kind of belief for a little longer? Indeed how could you, at that age, even get your head around a concept like suspending belief, of not going along with everything your parents tell you about something unseen?

When the real story was revealed to her, it was like a switch – and quite a painful one – from one of those pillars of childhood to an unfamiliar adult one. With no going back.

Many parents choose not to “deceive” their children with modern myths, like this tiny winged creature who takes charge of every baby tooth across the world. (Just do the calculations.)

Watching her be so upset, I wondered if we had done her a disservice. When her father and I chose to take the path of mythical beings – familiar to both of us from our own childhoods – we realised it was all or nothing. And that sometime it would end. When I was a child I remember the truth dawning on me slowly, from hints and comments of friends and older siblings, but it didn’t upset me. And I thought it was worth it.

My husband and I have chosen a mobile, rootless, family life for ourselves. We have adapted and made up some of our own traditions as we’ve moved our children from Canada to Norway to Italy to Ireland. We probably thought that Santa, the Tooth Fairy and just a hint of the Easter bunny would bring some stability from our own family backgrounds. And they have indeed proven to be a constant in our lives as we have moved language, friends, schools and houses.

What has been amazing to watch is how our two intelligent children have managed to go along with their parents’ official version of all these myths, for years, all the time ignoring what their friends around them in whatever country believed.

In Norway, for example, where we lived for most of their early childhood, everyone around us would expect Santa Claus to knock on their door and say “hallo” before handing over the presents – on the evening of December 24th, a full 12 hours earlier than us. But there was never any question in our house that Santa would graciously come, unseen, down the chimney (though we didn’t have one) during the night while we slept. And he certainly wouldn’t have looked like our neighbour in a red suit. What a notion!

Unlike the routines of Christmas, teeth can get lost at any time of the year. Anywhere. And so the tooth fairy has been our constant companion, moving and travelling the world with us.

We came up with a way to ensure the tooth fairy could always find us by explaining that a red light would show outside the window of any child that had lost a tooth that day. A red light that’s invisible to human eyes, of course.

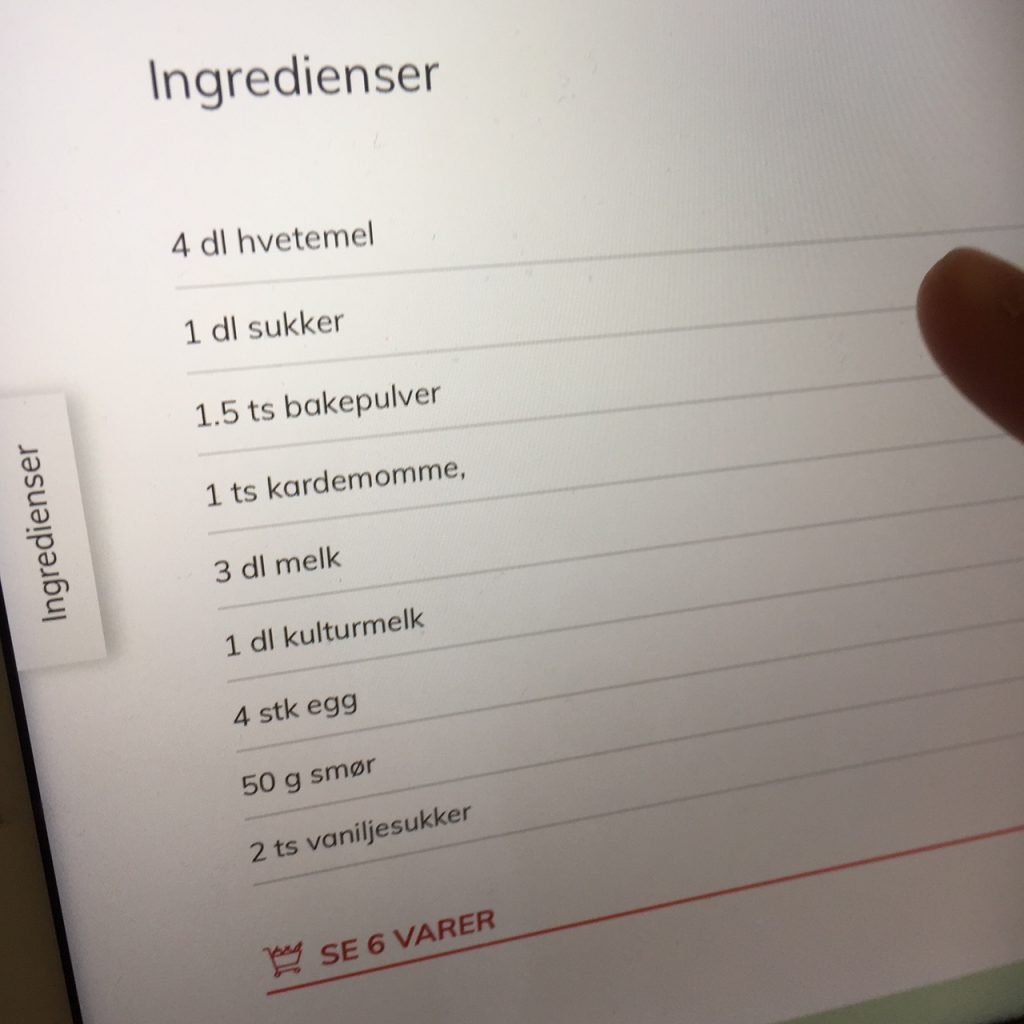

This fairy has been especially good at currency conversion depending on where the local pickup/drop-off needed to happen. The conversion isn’t totally accurate, but we wouldn’t expect her to carry change. 2 euro does not really equal 2 dollars (Canadian) nor indeed 2 British pounds nor 20 kroner (Norwegian or Danish). But this worked out to be a handy on-going maths and retail exercise for the kids, who always expecting the amount to be rounded up.

The most global adventure we dragged the fairy on was when our elder girl lost a tooth while we were visiting friends in Oxford during one big summer trip. She wanted to hold on to the tooth for longer so it came with us to Dublin – our next stop – and for some reason she wanted to get it all the way to her other grandparents’ house in Canada before finally agreeing to put it under her pillow and to trigger the red light there. She was thrilled to wake up to a two-dollar coin (a Toonie) the next morning and now she always associates that coin with that day.

Our younger, more rational, child (who I had thought was the one more likely to smell a rat) asked questions like: How does she carry all that money? Why only money and not also a present? Why doesn’t she come to grownups? The older sister would tell her that the fairy takes away all the teeth and builds up a great big store of them – but we’ve never figured out why.

A few times during our couple of years living in Italy, it came up that Italian children sometimes expect a tooth mouse, not a fairy, to come and collect their dental indiscretions. But we never heard much talk of it, and it doesn’t seem to have the same superstitious punch as the northern European tooth fairy.

So now, the tooth fairy has made an abrupt departure from our life but our girl has been assured that 4 euro (yes it’s gone up) will still be paid out for each tooth. She has yet to face up to dealing with the Santa issue, but she’s smart – it is only 3 weeks to Christmas and I can see why she’d let that conversation slide.

An old parental-guidance letter is doing the rounds again on social media this Christmas season, which begins with the words “Dear Daniel, you asked a really good question. Are mummy and daddy really Santa?… The answer is no, we are not Santa.” The letter goes on to explain that Santa is the spirit of Christmas, the magic and love and spirit of giving that is kept alive through parents. He lives in our hearts, not at the North Pole, and is there to teach young children how to believe in something they can’t see or touch.

Shall we go along with that advice, and stay close together as a family as we let the hard beliefs of childhood fall behind us and move on? I think we will.